What age do kids learn to write fluently is a common parental and educator question. In short: kids generally begin to develop basic writing skills between ages 2–5, move into emerging fluency between about 5–7 (Kindergarten to Grade 1), and reach more effortless, automatic handwriting and composition skills around age 7 and beyond, with steady refinement through the middle elementary years. True, effortless fluency — where letter formation is automatic and cognitive resources free up for higher-level writing — typically consolidates in later elementary (Grade 3+) as fine motor control, orthographic knowledge, and working memory mature.

The Importance of Writing Fluency in Childhood

Why this question matters Parents, teachers, and clinicians ask “what age do kids learn to write fluently” because writing is both a visible developmental milestone and a gateway skill for academic success. Writing fluency affects classroom performance, reading-writing connections, self-expression, and later academic outcomes. Understanding typical age ranges, the stages children pass through, and when to provide targeted support helps adults set realistic expectations and intervene early when needed.

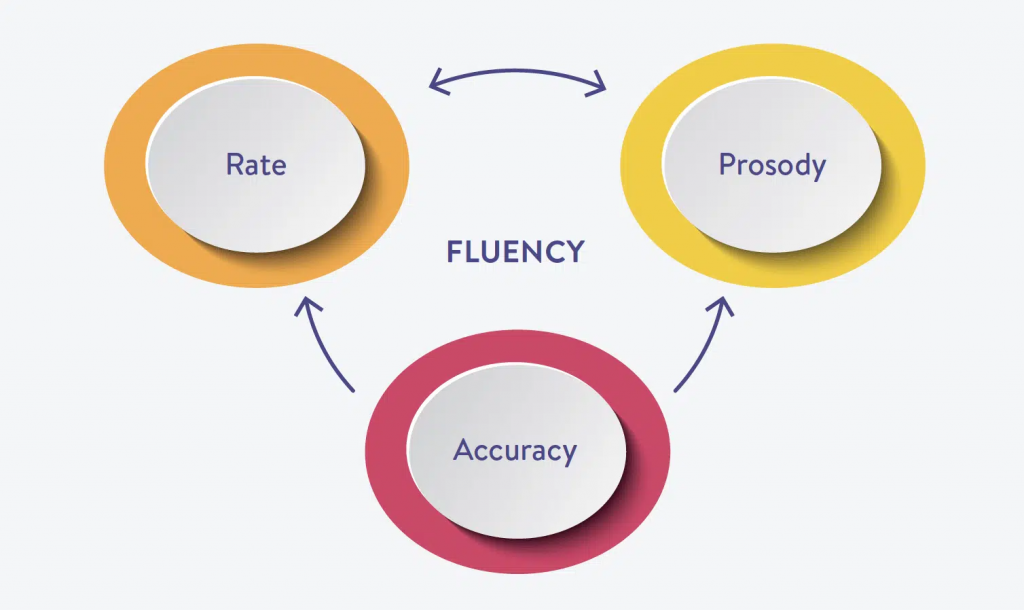

What “writing fluently” means Writing fluency is multi-dimensional. It’s not just neat handwriting. Key components:

- Automatic letter formation: letters can be produced with minimal conscious attention.

- Speed and legibility: writing at a pace that supports composition while remaining readable.

- Orthographic knowledge: conventional spelling (or rapidly developing spelling) rather than consistent phonetic inventions.

- Cognitive flow: working memory and attention devoted to ideas, not basic letter formation.

- Expressive competence: the ability to turn ideas into sentences and short paragraphs with appropriate grammar and punctuation.

These components combine differently at different ages. When teachers ask “is my student fluent?” they often consider letters-per-minute benchmarks, accuracy, and whether writing feels effortful.

Typical developmental timeline (detailed) Early Stages

- Ages 2–3: Scribbling and early tool use.

- Children explore marks, learn how to hold crayons and pencils, and begin controlled scribbles. Grip and posture develop; early scribbles are the foundation for later letter-like forms.

- Ages 4–5: Shapes, emergent letters, and name writing.

- Kids draw circles and simple shapes and begin forming letter-like shapes. Many can write some letters and often write their own name, frequently using phonetic approximations (for example, writing “KT” for “Katie”). They may label pictures and compose single-word attempts.

Developing Fluency (Ages 5–7 — Kindergarten & Grade 1)

- Transition to true letter formation and early sentence writing.

- Children typically begin writing simple sentences with basic punctuation (capitalization and a period) and use letter-sound relationships to spell (phonetic spelling). Sight words such as “the,” “and,” and “is” become recognized and spelled more accurately.

- Narrative and explanatory skills emerge.

- With guidance, kids write short narratives (who, what, where) and simple explanatory pieces. Writing remains effortful at times; letter formation competes with the mental load of ideas, phonics, and spelling.

- Fine motor and orthographic gains accelerate.

- As fine motor control improves, handwriting becomes smoother and faster; by the end of this period, many children can write short, legible paragraphs.

Fluent Writing (Ages 7+ — Grade 2 and beyond)

- Orthographic convention and automaticity increase.

- By around age 7–8, spelling becomes more conventional (invention decreases), and handwriting shifts from conscious letter-by-letter production to more automatic reproduction.

- Cognitive resources shift to content and revision.

- Children devote more attention to planning, vocabulary, grammar, and organization rather than struggling with letter formation. They write longer passages, try different genres (stories, opinions), and begin to revise their own work.

- Ongoing refinement through upper elementary.

- Fluency continues to improve: faster transcription, improved punctuation and paragraphing, and more sophisticated sentence structures. However, full maturation of written expression continues into later schooling.

Kids generally develop writing fluency, moving from simple words to full sentences and stories with better spelling and grammar, between ages 5 and 7, though the truly effortless, automatic stage (like middle schoolers) comes later, with significant growth in early elementary (grades 1–2) as fine motor skills mature and they grasp phonetic rules. This staged progression aligns with research tying motor, cognitive, and linguistic development to writing outcomes.

Developmental Foundations of Writing Fluency

Developmental skills that enable writing fluency Writing is an intersection of motor, language, and cognitive systems. Key contributors:

- Fine motor control and hand strength: permit consistent, legible letter formation and adequate speed.

- Visual-motor integration: coordinates what the child sees with hand movements (helps spacing, alignment).

- Phonological awareness and orthographic knowledge: support spelling from sound to letter patterns and sight word recognition.

- Working memory and attention: allow holding sentence structure and word choices while transcribing.

- Language skills: vocabulary, grammar knowledge, and narrative competence underpin composition.

Educational and environmental influences

- Instructional approach: Different curricula (e.g., Montessori, traditional phonics-based programs) emphasize varied sequences and practices. Schools that start earlier with structured handwriting and phonics may see earlier gains in conventional spelling and basic fluency, but individual differences remain large.

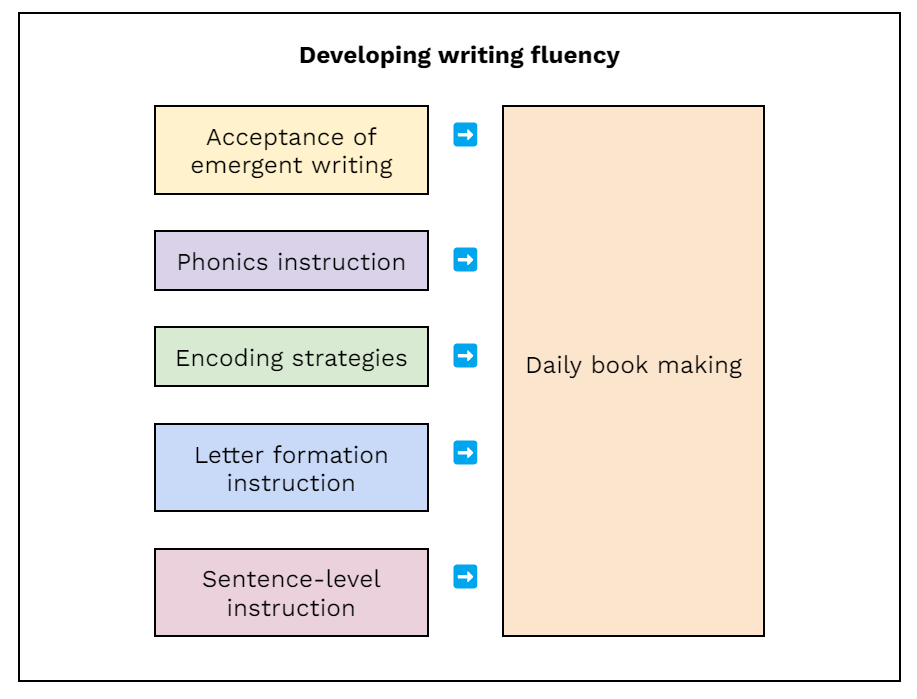

- Practice quantity and quality: Frequent, meaningful writing (journals, storytelling) and targeted handwriting practice accelerate fluency. Practice that emphasizes both accurate formation and purposeful composition is most effective.

- Technology: Keyboarding skills develop alongside handwriting. Some schools balance both; research suggests initial handwriting practice supports letter recognition and spelling, while keyboarding becomes an important complementary skill.

- Individual factors: Bilingualism, giftedness, and socio-emotional context can influence pace. Access to books, parents’ engagement, and early childhood programs all play roles.

Common milestones and classroom expectations by grade Preschool (3–5)

- Scribbles evolve into shapes and letter-like forms.

- Children show interest in print and often attempt their name by age 4–5.

Kindergarten (5–6)

- Most children form many letters correctly.

- Begin writing short words, simple sentences, and using letter-sound knowledge.

Grade 1 (6–7)

- Writing of full sentences with punctuation becomes common.

- Many children can write short narratives and spell common sight words accurately, though phonetic spellings remain.

Grade 2 (7–8) and beyond

- Spelling becomes more conventional; invented spellings decline.

- Transcription speed supports composing longer texts; children experiment with genre and revise independently.

When to Be Concerned About Writing Fluency

When to be concerned: red flags and possible causes Not all children follow the exact timeline. Red flags that may warrant evaluation:

- By age 6–7, persistent illegible letter formation and extremely slow speed that impedes schoolwork.

- Continued severe letter reversals, spacing problems, or inability to form letters despite practice.

- Excessive fatigue, avoidance of writing activities, or extreme discomfort with pencils.

- Significant discrepancy between oral language ability and written expression.

Possible underlying causes:

- Developmental Coordination Disorder (dyspraxia) affecting motor planning.

- Dysgraphia: a specific learning difficulty in written expression.

- ADHD: affecting attention and persistence during writing tasks.

- Visual-motor integration or vision issues.

- Language-based learning disabilities affecting spelling and composition.

Recommended actions:

- Classroom accommodations (extra time, alternative transcription methods).

- Occupational therapy for fine motor and sensory-motor interventions.

- Educational evaluation for specific learning disorders.

Practical tips for parents and teachers to build fluency Fine motor and pre-writing activities

- Play-based hand strengthening: playdough, tweezers, stringing beads.

- Finger isolation games: picking up small objects, buttoning, peg boards.

- Scissor skills and cutting activities to improve bilateral coordination.

Effective Practices for Writing Development

Letter formation and handwriting routines

- Teach letter formation with simple, consistent models (start stroke, direction).

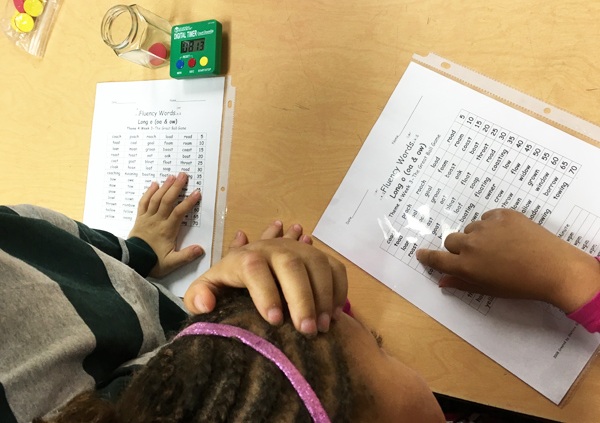

- Short, daily handwriting practice — 5–10 minutes of focused, meaningful practice beats long, infrequent sessions.

- Multi-sensory approaches: writing letters in sand, tracing while saying letter sounds.

Writing for purpose

- Encourage written storytelling, lists, labels, and short journals to make writing meaningful.

- Use prompts that relate to children’s interests to reduce cognitive load and increase motivation.

Structured programs and classroom strategies

- Use graded handwriting programs that integrate posture, grip, and formation.

- Implement sight-word instruction in tandem with phonics to boost automatic spelling.

- Pair handwriting instruction with composition tasks that emphasize idea flow, not just transcription.

Comparisons that matter to parents

- Montessori vs. traditional: Montessori often emphasizes fine motor and sensory preparation that can support early letter formation; traditional programs vary but often include systematic handwriting instruction in early grades.

- Cursive vs. print-first: Many schools teach print (manuscript) first; evidence about cursive accelerating fluency is mixed. Cursive may help some students with flow and speed, but mastery depends on instruction quality and practice.

- Extra practice vs. classroom instruction: Targeted interventions (OT, focused handwriting programs) can produce faster gains than general classroom exposure alone for children with delays.

Research-backed data and authoritative guidance

- Developmental milestone guidance (e.g., CDC early milestones) indicates that many prewriting and early writing behaviors appear by age 4–5, with more advanced transcription skills developing in early elementary grades.

- Occupational Therapy and school-based research find that improvements in fine motor control and visual-motor integration correlate with better handwriting legibility and speed.

- Education studies show that early phonics instruction supports conventional spelling, which in turn frees cognitive resources for fluency and composition.

Examples and cases

- Typical progress: A child who begins intentional letter practice at age 4 (name writing, letter formation), with daily emergent writing activities, often writes simple sentences independently by age 6 and produces short paragraphs by age 7 with improving spelling and punctuation.

- Child with delays: A child with fine motor delays who receives occupational therapy and targeted handwriting instruction may show rapid improvements in legibility and speed within months, enabling better content focus.

- Teacher’s benchmark: Many K–2 teachers expect most students to reach functional handwriting fluency by the end of Grade 2, though they allow for a range of individual trajectories.

Recommended Resources

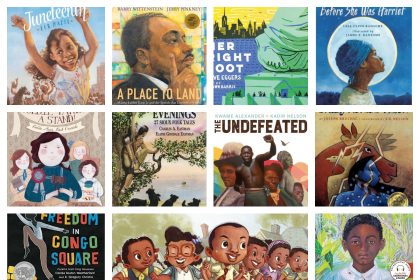

Trusted reading libraries and leveled book collections to boost vocabulary and writing ideas – including Epic: The Leading Digital Reading Platform for Kids, built on 40,000+ popular, high-quality books from 250+ of the world’s best publishers, designed to safely fuel curiosity and reading confidence for kids 12 and under.

In addition to Epic, leveled reading libraries and classroom-style book collections help children progress from simple texts to more complex narratives in a structured way. These resources reinforce phonics, expand sight-word knowledge, and introduce new sentence patterns, which directly supports writing development. Regular exposure to age-appropriate, high-quality books not only strengthens reading confidence but also gives children concrete ideas for their own stories, descriptions, and creative writing projects.

FAQs

What age should a child write fluently?

A reasonable expectation is that children begin to show writing fluency between ages 5 and 7, producing full sentences and short narratives with growing spelling and punctuation consistency; however, more effortless automaticity — where letter formation no longer consumes cognitive effort — generally emerges in later elementary (around Grade 3 and beyond). Because development varies, “fluency” should be judged against multiple factors: legibility, speed, and the child’s ability to focus on ideas rather than letter shapes.

Should a 6 year old be able to write his name?

Yes, it is typical for a 6-year-old to write his or her name legibly and with increasing consistency. By kindergarten and first grade, most children can write their name using recognizable letter formation, though some may still use phonetic spellings or show variability in letter size and spacing.

Should 7 year olds be able to write?

By age 7 (often Grade 2), many children can write short paragraphs, spell common words more conventionally, and demonstrate less effortful handwriting. They typically produce longer pieces than in earlier years and begin to focus more on content and sentence structure, though continued improvements in neatness, speed, and punctuation are common through later elementary.